ANDREA BAKER

|

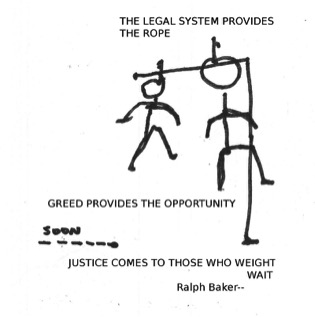

I’ve been hanging up the phone for two years, but there’s an indomitable spirit to the deluded. I’m getting ahead of myself. You can go to Bermuda, or Paris, or San Paolo. Buy a ticket. Pack your luggage. Maybe take a Valium for the flight. Have a honeymoon, maybe. Get drunk, maybe. Bring home souvenirs. A pebble from the beach.... A t-shirt. The kind of stuff that ends up in second-hand shops. A shell-decorated box. A branded leather belt. The point is to get away, escape; this is not a noble travel. Certainly not a soldier’s travel. Or, you can travel by staying in the same place and forcing the world around you to change. In this way, a spaceship doesn't need an engine; the sheer force of you and your actions in the world can recreate the space around you. Ralph was a Soldier and a Space Cadet. So were Rosa Parks, Abraham Lincoln, and Gandhi. I liked this idea. I figured it happens--we'd have no use for the Nobel Peace Prize if it didn't happen. If it didn't happen, we'd roll over. We'd wake, drink coffee, do our best to wear clean clothes, find our shoes, find the keys, and throw ourselves, if not off a bridge, out of our threshold and into the world built for us. We'd join hands with our neighbors in the real-world delusion. Keep our money in the bank. Shop for groceries at the store. PTA. Picture day. Halloween parade. The Polish importer had cans: canned beans and canned sauerkraut and the frozen shrimp that Ralph washed the breading off then ate with cheap noodles. The Italian guy on Metropolitan Avenue had the cheese—fresh mozzarella still cold in the wrapper—and jars of antipasto and bottles of vinegar. Bread came from Moesha’s. Every afternoon around 4:30 there was at least one of our favorites: pumpernickel, sunflower seed, or walnut raisin. The Asian importer was fun for candied walnuts, soymilk, ginseng capsules, and dried mushrooms. But really, it was the tomato dumpster—the one I found on my own—that I cherished. Hydroponically grown, perfectly ripe today, so they’ll be no good by the time they get to market, tomatoes. Everyday around 4:00 Lucky’s Real Tomato put out two dumpsters full. Every now and then we got the boxed cherries—golden or red. And we were wealthy, with trash bags of surplus fruit to bring our friends. He tells me he’s on death row. A chemical lobotomy is pending. But, he’s still sure he can use the moment in front of the judge to get his quiet title. I’m thinking that any mention of real estate is only going to reinforce why he should be held. And if there’s anyone he’ll listen to it’s me, but I don’t tell him what I think. I’m accustomed to not arguing with things that don’t make sense, and I want them to keep him. She tells me that he’s paranoid. When I ask for examples she says it’s not that he has any particular or recurrent paranoid thoughts, but that his overall scheme and way of relating are characterized by paranoia. She suggests that if I look for it, I’ll begin to see a theme of persecution. Because he acts as if nothing is a problem, it’s difficult for me to imagine him having problems. But, of course, his problems have become catastrophic. I get a call from another friend telling me she was passing by the building as a team of men loaded all of Ralph’s possessions onto a truck. They’d deconstructed the glass and steel structure he called his Spaceship. I tell her that I’ll break the news and plan to go in person to do so, but then I don’t. I tell him on the phone. And I begin to argue with him too. Now there’s a new type of freedom, a freedom to discern. When I stare at myself I only want to see. I replay a conversation in order to observe the facial expressions it evokes. I look sad and withdrawn, trying to leave one eye downcast while I bring the other up toward the mirror so I can see what sad and withdrawn look like. That’s what I want to see more than anything—myself trying to pull away from the world. The two men are not related. The older Baker even convinced a bail bondsman he owned the apartment building and used it as collateral to get released from jail.” I spent the next day in quiet, steady tears. My tears road with me on the train. They lay down with me when I rested. They washed the dishes and fed the cat and brushed my hair. By “Soon,” Ralph meant another month until he got title to his building, an event that has yet to happen, though he never stopped believing. *

He had come to be blind slowly. Glaucoma surgery could have stopped it. When he could see, he was a street photographer. Whenever he went missing for a couple days we assumed he was in jail. Before his lawsuits were about real estate, they were about photography. Bery v. City of New York, 97 F.3d 689, 698 (2ndCir.1996) held that it was a violation of the first amendment to restrict artists from selling their goods on public sidewalks, but it also held that, for certain high traffic areas, like Time Square, First Amendment Vending could be banned. Ralph liked to shoot photos of tourists in Time Square. If photography is an art, it is subject to the rules established in Bery. If photography is not an art, the photographer needs a permit from the Mayor’s Office of Film Theatre and Broadcasting. Ralph’s lawsuits were about trying to convince a judge that he is not an artist, and that the Mayor’s Office should be ordered to issue him permits. Once he was no longer capable of typing, I began typing for him. He taught me how to make requests of the Court in the form an Order to Show Cause and how to write Affidavits in support of the aforementioned Orders. Then I call him on the phone and I tell him that the doctor is right and that he’ll never get the building. He interprets my disagreement as persecution and hangs up on me. Gothamist, Sept 10, 2005: “There is no other way to put it. Ralph Baker, street photographer, is simply not your average kind of guy. He lives in what he calls his ‘spaceship,’ a green-housed, alternative, post-apocalypticish living space wedged snugly between two Williamsburg residential/commercial buildings. Ladders connect ‘floors’ together. There's the gadget filled ‘engine room’ in the basement... Con-Ed supplies his gas and Verizon supplies his phone service.” Gothamist asked him: “You're a street photographer, but you're legally blind...”

Then I’m putting the phone back into my pocket, back onto my desk and back into my bag. And I have still neither listened to the full message nor blocked the number.

|